6 Ways To Save U.S. Startups And Jobs From Death By Regulation

If the Internet makes it easier than ever to start a company, why are fewer of them getting started today?

In the last two decades, software has become more functional and smarter, and many small-business services are now available free online. Customers for niche products are easier to find and serve globally. Entrepreneurs generally need less funding to get started and can more easily identify and qualify funding sources. Entire departments can be outsourced or automated. Skills can be learned free through online courses. All of these things have made starting businesses easier. But one main thing has made starting businesses harder: government regulation.

In 1992, when I started my first company, you could freely hire a programmer or other contractor for as many hours or days per week as you could afford and as the individual was available. As you grew, you could gradually increase the hours the contractor worked until you could afford to make him or her an employee. It made starting a cash-strapped business possible. Not so today.

Today, complex and subjective rules govern whether any worker, even one working just a few hours a week, is considered a contractor or employee. If employee, you must withhold income taxes, withhold and pay Social Security and Medicare taxes, pay unemployment taxes, and comply with countless other laws, rules and regulations. Each has its own myriad supporting documents and forms, for example, the six-page Form SS-8 (“Determination of Worker Status for Purposes of Federal Employment Taxes and Income Tax Withholding”).

Satisfying the IRS that your contractor is a contractor often requires a tax specialist or attorney, or having another firm hire the contractor as an employee and contract that person to you—a significant management burden and expense in either case. Worker status law reflects a focus on maximizing collectable taxes; none on business practicality or compliance costs. For any entrepreneur, a costly hassle. For a first-time, cash-strapped entrepreneur? Probably overwhelming, possibly insurmountable.

Start-ups provide jobs for both their founders and their employees. An important few grow into sizable businesses. According to the SBA, businesses with fewer than 500 employees create 64% of net new private-sector jobs. Estimating Entrepreneurial Jobs: Business Creation is Job Creation says that key to job creation is not company size but youth – how recently the business was founded. Older firms, whether large or small, tend to have stable headcounts; most of their growth comes from acquiring younger companies. Young firms energize the workforce. But they are a rough and tumble world: over half of startups go out of business within five years. Net job growth comes from the survivors. Beyond their role as job creators, start-ups provide choice in products and services, and drive innovation and economic growth. When there are plenty of entrepreneurs, start-ups broadly distribute wealth throughout society. And when many startups are being created, job growth adds up. Even the two small companies I founded, Decisive Technology and CustomerSat, together employed over a hundred full-time professionals and provided many more jobs to contractors before they were acquired.

That’s all good news. The bad news is that, despite popular belief, entrepreneurship in the US has been on a precipitous decline for the last 25 years. According to a study of the Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Business Database by the New America Foundation, the number of new businesses created for every 10,000 working-age Americans has declined from approximately 27 in the 1980s to 25 in the 1990s to 22 in the 2000s. Using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the study also showed that the percentage of working-age Americas who are self-employed has dropped by 13.6% from 1994 to 2011. As a percentage of all businesses, new firms have dropped from 16% in 1977 to less than 8% in 2010.

Many other regulations burden entrepreneurs besides worker status, of course. IRS tax liens, minimum wages, Equal Opportunity, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) are examples. Added to these are myriad state, local, and industry-specific regulations. Bob Luddy, founder and CEO of CaptiveAire, says that most of the regulations governing commercial kitchen ventilation date to the 1950s, well before demand ventilation, solid-state controls, or new motors were invented. As a result, he says, most of the R&D in his industry goes not into innovation — improving kitchen ventilation — but into compliance with outdated regulations.

The 2012 Code of Federal Regulations’ 174,545 pages increased by over 21% in a decade, according to the Congressional Research Service. Which regulations most burden entrepreneurs? If you develop software, they may be strict quotas limiting visas under which overseas professionals can work in the US. If you deliver parcels, they may be federal and state transportation laws. If you are a construction contractor or building owner, likely OSHA and ADA compliance. Close friends of mine founded a restaurant chain that now employs hundreds of teenagers and other less skilled workers. Rising minimum wages are putting them out of business; they have put the chain up for sale.

For any metric combining skill, luck, ambition, resources, passion, and self-confidence that you choose, many entrepreneurs—perhaps most on the low end of your scale—are being eliminated by regulation. Given entrepreneurship’s essential role in creating jobs, coupled with incentives not to work, it’s not surprising that we have high unemployment.

The very regulations that create unemployment in the US are a boon to employment and quality of life overseas. Jobs and innovation tend to flow to the least heavily regulated jurisdictions and countries. A majority of startups developing medical devices that require FDA Premarket Approval (PMA) now begin selling in Europe first, where CE mark compliance is easier and faster to achieve, according to Fred Dotzler of De Novo Ventures. This gives Europeans earlier access to new medical technology than Americans, and the European medical device industry a home-field advantage.

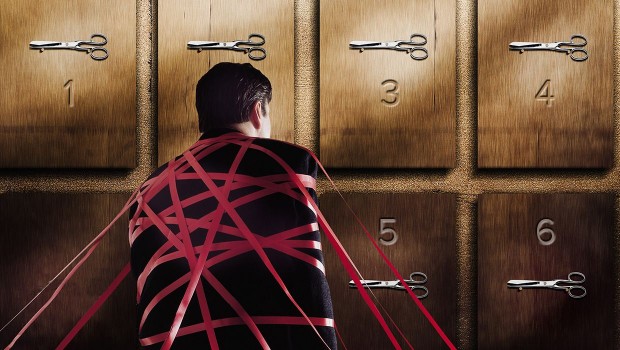

With such a dense tangle at multiple levels, eliminating even dozens of the worst regulations, while a positive step, would seem alone unlikely to reverse declining US entrepreneurship. Rather, we need a sustained, bipartisan attack to elevate awareness, repeal or allow thousands of regulations to expire, and adopt new mindsets of extreme forbearance in enacting new regulations. None of this will be easy. My recommendations:

- Field test regulations before enacting them to ensure that they are readily comprehensible and that their costs and unintended consequences do not offset their intended benefits. This asks no more of the law than any business routinely undergoes to ensure quality and acceptance of its products or services.

To determine if a regulation is readily comprehensible – a test that worker status and many others would have easily failed – see if small-business owners can re-state it accurately in their own words. A simple law is not necessarily good, but a complex law is almost certainly bad. Business owners should not have to hire experts to interpret regulations or plead for exemptions. Both of these invite corruption and further concentrate wealth in the hands of the few who are adequately funded, suitably connected, or sufficiently influential to seek and win favorable interpretations or exemptions.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) perversely incentivizes business owners to convert formerly full-time employees to part-time status, bad for businesses and employees alike. Field-testing would likely have revealed this.

Conduct Innovation Impact Assessments. Doing this will be challenging, as are Environmental Impact Assessments that try to predict how wildlife will co-evolve over years with real estate developments and landscaping. Both innovation and the environment are complex adaptive systems with chaotic aspects that simply cannot be predicted. But where a regulation’s impact on innovation can be documented or predicted, it should be included in regulatory review and approval. At the Neurogaming 2013 conference, panelists openly shared tips on how to avoid the FDA. If your game measures heart rate, don’t advertise that fact; otherwise, the game may be considered a medical device. Not just innovation but a promising new US industry is being threatened. Has the ADA’s requirement for wheelchair ramps slowed development of smart, low-cost prosthetics that allow the disabled to comfortably negotiate stairs? If so, the ADA may be disabling the disabled.

Include a sunset clause in every statute that specifies its automatic expiration date. Technology is changing our lives at an ever-increasing rate, so the period of time a law goes unreviewed should also systematically decline. My suggestion: let every regulation expire in no more than 20 years, with the limit declining continuously by 10% every decade starting now. For a regulation enacted in 2023, the limit would be 18 years. If one enacted in 2013 still makes sense in 2033, let it be explicitly re-enacted then (for up to 16 years).

Let every regulation be as local as possible, thus making legislators and regulators most accountable for benefits exceeding costs and amending or repealing regulations when they don’t.

Learn from those different local jurisdictions. See what works and doesn’t; copy what works. Federal regulations provide nation-wide uniformity, but are unlikely to improve our lives without test, feedback, elimination, and renewal. We learn more, faster when we run multiple experiments in parallel. Better to return to the 50 state legislatures the freedom and responsibility to make their own regulations and let the States learn from and copy each other. Cities do this best, adopting successful park service, highway maintenance, public transportation and police arrangements from each other.

Trust market forces and common law traditions that already regulate business and trade and have withstood the test of time. Supply and demand. Word of mouth. Private contracts. Tort law. Such market forces and traditions are generally simple and comprehensible, reflect widely accepted norms and practices, and have the fewest unintended consequences. When you layer on multiple levels of complex regulations, you get a legal morass that creates uncertainty and cost, stifles entrepreneurship and innovation, causes unemployment, and narrows the distribution of wealth.

I’m holding off on starting another company for now. It is hard enough to find a market niche, differentiate your product or service, attract capital, find customers, and deliver value. Let’s not let runaway regulation further jeopardize our precious startups’ already precarious existence.

[1]In Simple Rules for a Complex World, law professor Richard Epstein says, “Never ask more from a legal system than covering 90-95% of the cases; the effort to clean up the last 5% leads to the system’s unraveling.” With worker status, the IRS appears to me to be trying to cover 99.9999999999% of the cases.

[2]Small Business Administration and Job Creation, Congressional Research Service, January 30, 2013.